I wouldn’t let the nurses take my granddaughter from my arms—not until I was done holding her.

She looked flawless: ten tiny fingers, ten perfect toes, my girl’s nose, my late wife’s stubborn little chin. She arrived at thirty-seven weeks without a sound. The doctors said nothing could’ve prevented it.

Sometimes, they told me, babies don’t make it. But I gathered her close anyway—the granddad she’d never meet—and hummed the lullabies I’d once sung to her mother three decades earlier.

My daughter was sedated and bleeding, fighting to stay with us. Her husband passed out the moment the words “no heartbeat” landed.

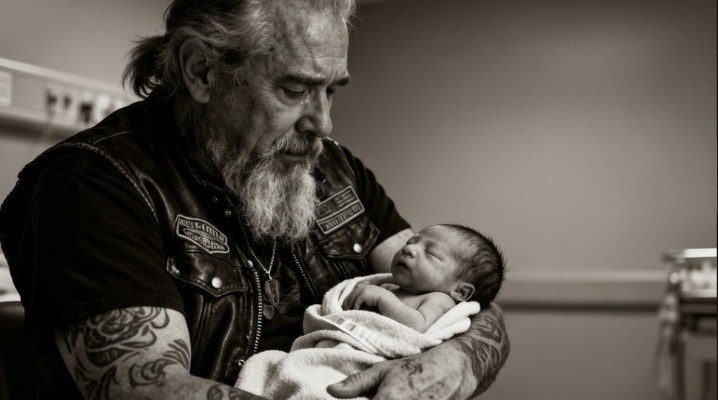

So it was me—sixty-nine, a leather-vested, tattooed old rider—cradling a perfect child who would never open her eyes.

The funeral home representative came and reached toward her. I tucked her against my chest and murmured, “Not yet.”

“She needs to feel love. Even if it’s only these two hours—she needs someone to hold on to her.”

What followed in that hospital room reshaped how an entire NICU responds to infant loss.

Her name was meant to be Lily.

Lily Marie Henderson—named for my wife, gone three years now from ovarian cancer. My daughter, Emily, had painted butterflies across a yellow nursery because she’d wanted the surprise. I spent three weekends getting those wings just right. We’d set a family rocker in the corner; it was my wife’s, and her mother’s before that.

I’m Tom “Ghost” Walker. Sixty-nine. Vietnam veteran. Mechanic. Forty-one years on Harleys. Widower. Finally about to be a grandfather.

At least, that’s what we believed.

Emily called at 2 a.m. “Dad, something’s wrong. I can’t feel her.”

I sped through the night like the road owed me a miracle. The four miles took forever. Triage was a blur—Emily pale and shaking, Brian white as paper, nurses moving with that tight urgency you learn to fear.

“No heartbeat,” the doctor said, flat as a weather report.

Emily made a sound I’ve only ever heard in war—raw, animal, world-ending.

“We have to deliver now,” the doctor continued. “The baby needs to be delivered, and Emily’s showing signs of placental abruption.”

“She,” I said. “Her name is Lily.”

He looked me over—old biker, gray beard, leather vest. “Are you the grandfather?”

“I am.”

“Perhaps you should wait outside.”

“Not happening.”

Emily grabbed my hand. “Dad stays. Or I don’t do this.”

The birth was the quietest thing I’ve ever witnessed. No cries, no cheers—just monitors beeping and my daughter’s broken sobs. Brian fainted when they lifted Lily free; nurses caught him before he hit the floor.

And there she was.

Beautiful. Whole. Silent.

A nurse swaddled her and started to carry her away—then Emily hemorrhaged. Alarms shrieked. They rushed my daughter to surgery.

“Take care of her, Dad,” Emily gasped as they wheeled her out. “Don’t let them just take her. Please.”

So there I stood. Brian unconscious. Emily in an OR. And a nurse holding my granddaughter.

“Would you like to hold her first?” she asked gently. “Before we take her?”

Before we take her. Like she was a package to be processed.

“Yes.”

They set Lily in my arms—six pounds, four ounces of softness. Dark hair like Emily. My wife’s nose. Warm still, the kind of warmth that tricks your mind into waiting for a breath.

“I’ll give you a few minutes,” the nurse said.

A few minutes to say farewell to a future we’d painted butterflies for. A few minutes to understand that the mobile I’d hung would never spin over a sleeping baby’s face.

I sank into the chair and studied her features. “Hey, little one,” I whispered. “I’m your grandpa. The one with the loud bikes.”

Emily had put headphones on her belly every night—recordings of my voice and old clips of Marie, so the baby would know us.

“Your grandma would’ve adored you,” I told her. “Her hands were soft—nothing like these.” I looked at my knuckles, scarred and oil-stained from a lifetime of engines, somehow holding something so delicate without breaking.

Thirty minutes later, the funeral director showed up—polite face, black suit.

“Mr. Walker? I’m here for the baby.”

“No.”

“I understand this is difficult—”

“You don’t. My daughter’s in surgery. Her husband’s out cold. And you want to take this child to a cold room? No.”

“Sir, there are procedures—”

“I don’t care about your procedures.”

I unzipped my jacket and nestled Lily against my chest. My body heat chased away her chill.

“Sir, you can’t—”

“Watch me.”

Security arrived, two young guards who took one look at an old man in leather, crying with a baby tucked inside his vest, and decided rules could bend. “Let him be,” one said softly.

A senior physician came next. “Mr. Walker, I’m sorry—”

“My granddaughter was born forty minutes ago. My daughter might die. And all I hear is process, process, process. She was real. Treat her like she was real.”

The doctor looked at Lily’s face peeking from my jacket. “Two hours,” he said. “Then we must transfer her.”

“Two hours,” I agreed.

We were alone again.

I started talking—everything I’d hoped to share over years. I told her about her grandma: how Marie danced while she cooked, how she could pull laughter out of the darkest rooms, how she faced cancer braver than any soldier I knew.

I told Lily about the bike with the sidecar I’d bought, “for when you’re older,” I’d told Emily, so we could putter around town. It sat in my garage, gleaming and useless.

I told her about Vietnam—things I’ve never said aloud—about a village near Da Nang and a little girl who bled out in my arms while I screamed at the sky. “You aren’t her,” I whispered to Lily. “You’re not a failure I couldn’t fix. You’re my granddaughter. And while I have you, you are warm and safe and loved.”

I sang to her, off-key and stubborn—“You Are My Sunshine,” then “Blackbird”—old songs Marie had sung to Emily, my voice cracking in every chorus.

A NICU nurse slipped in—mid-fifties, steady eyes. She sat beside me. “I lost a baby at thirty-two weeks,” she said. “Twenty-three years ago. It still hurts.”

“Does it fade?”

“It changes. It never really fades.”

She looked at Lily and smiled. “She’s beautiful.”

“She is.”

“Would you like photos? I have a good camera—for your daughter. For later.”

I nodded.

She came back with a real camera and took portraits: Lily’s hands, her feet, a close-up of that tiny mouth. Then she returned with a basin of warm water, soft cloths, baby shampoo.

“Every baby deserves a first bath,” she said.

We bathed her together, slow and reverent. The nurse showed me how to support her head, how to wash the wisps of hair. We dressed her in a pink onesie, a bow hat, little booties.

“Now she’s ready,” the nurse whispered. “When you are.”

An hour later, they rolled Emily from surgery—groggy, pale, alive. Brian was awake too, shame-faced and shaking.

“Where is she?” Emily rasped. “Where’s my baby?”

I placed Lily in her arms.

“She’s perfect,” Emily sobbed, rocking her. “She’s so perfect, Dad.”

We told Lily about the nursery and the butterflies and the chair in the corner. Brian finally gathered her up and wept like I’ve never seen a grown man cry.

Emily was fading; meds pulled her under. “Dad,” she whispered, clinging to Lily, “don’t let them take her too soon.”

“I’ll stay,” I promised. “I won’t let her go alone.”

The funeral director returned long after our two hours. He saw Emily, half-conscious, still trying to memorize her daughter’s face.

“Ten more minutes,” I said. It wasn’t a request.

He nodded.

When Emily finally fell asleep, I lifted Lily once more. The director reached out.

“I’ll carry her,” I said.

“Sir, we typically—”

“I’ll carry her.”

He studied the old biker who wouldn’t yield and stepped back. “Okay.”

I walked with Lily through the hospital—past the NICU where she should’ve been, past the nursery window where families pressed their palms to glass, down the elevator to the cool, quiet basement. I laid her on the table myself, kissed her forehead, smoothed her blanket.

“Thank you,” the director said softly. “For showing me what dignity looks like.”

We buried her four days later in a casket so small it felt unreal. Emily asked for my brothers to come—“Dad’s family.” Forty-three bikes lined the cemetery road, leather vests and patched jackets forming a circle around a grave the size of a suitcase.

The pastor stumbled; how do you eulogize a life with no minutes? So I spoke.

“Lily Marie lived two hours in my arms,” I said. “In that time, she was loved more fiercely than some folks are loved in a lifetime. She was sung to and bathed and dressed. She heard her mother’s song and her father’s cries. She existed. She mattered. She was real.”

After the service, the NICU nurse found me—the one who bathed Lily.

“We’re changing our approach,” she said. “Because of you. Because of Lily. Parents can keep their stillborn infants as long as they need. We’re setting up a dedicated room—a rocker, a bed, soft light—so families can say goodbye properly.”

“What will you call it?” I asked.

“The Lily Suite.”

Emily cried again—this time, from a place with sunlight in it.

That was three years back.

Last year Emily delivered a healthy boy—lungs like sirens, very much alive. We named him Thomas. Still, Lily’s nursery remains exactly as it was: butterflies, yellow walls, empty crib.

“I can’t take it down,” Emily says. I don’t push. The sidecar in my garage is still polished, waiting for a passenger who won’t arrive.

Every October 15th—Lily’s day—we ride. Forty-three of us, engines low, to the cemetery. No speeches. Just leather and silence and a wind that smells like rain.

Brian asked me once why I dug in my heels that night. Why it mattered.

“Because for two hours and seventeen minutes,” I told him, “she was my granddaughter—not a case number, not an unfortunate outcome. She was Lily. And Lily deserved arms.”

The hospital says dozens of families have used the Lily Suite since. Parents holding and bathing their babies; siblings counting fingers and toes; time stretching long enough for love to leave a mark.

Emily’s pregnant again—a girl, due in three months. She’s terrified.

“What if it happens again, Dad?”

“Then we’ll hold her, too,” I say. “As long as we’re allowed. And she’ll know she was loved.”

“How are you so strong?”

I think about war and widowerhood and the weight of a small body growing cold.

“I’m not,” I say. “I’m just stubborn. I won’t let the world tell me the schedule for love or grief—or how long I’m permitted to hold my granddaughter.”

Last week, a young couple lost their baby. The nurse called me. Would I come talk?

I found them in the Lily Suite, cradling their son. The father looked at my old, inked hands and said, “They told us you started this.”

“My granddaughter started it,” I said. “I just refused to let go.”

“How long did you hold her?” he asked.

“Two hours and seventeen minutes,” I answered. “And I would’ve held her forever.”

The mother whispered, “Does it ever stop hurting?”

“No,” I said honestly. “But somewhere, there’s a little girl named Lily who lived two hours and changed this place for families like yours. That matters.”

I left them there—door closed, lights low, time doing what time must.

Because that’s Lily’s lesson: love ignores clocks; grief ignores forms; sometimes the holiest thing you can do is refuse to loosen your grip until your heart says it’s time.

Two hours and seventeen minutes.

That’s how long I held my granddaughter.

Some would say that’s too short to matter.

They’re wrong.

Those two hours and seventeen minutes changed everything—for me, for Emily, for every family who’s sat in that room, for every child who’s been held instead of hurried away.

Two hours and seventeen minutes.

That’s how long Lily lived.

And every second counted.